Donika Kelly’s new collection digs into love, memory and the bones we carry

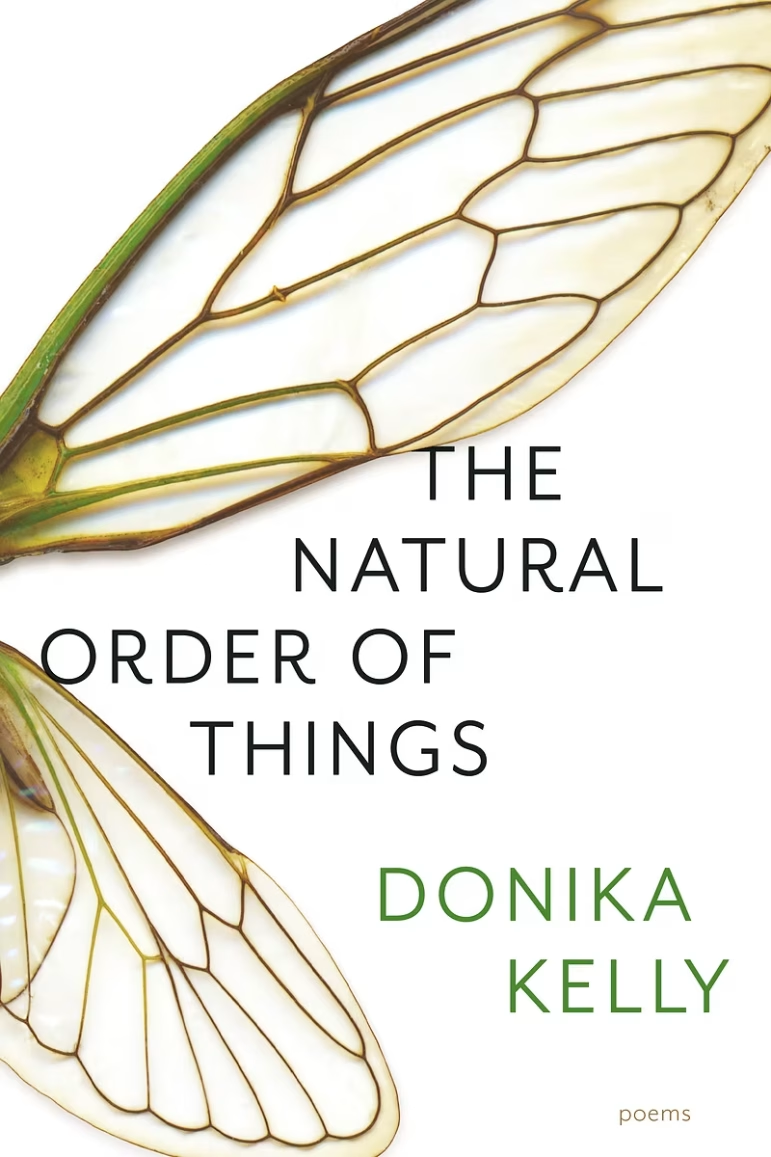

In “The Natural Order of Things,” poet Donika Kelly threads the intimacy of Black family life, queer love and ancestral memory through a recurring image of bones. Her latest collection explores healing, desire and the natural world with clarity and depth, inviting readers to feel how love and survival reverberate through the body.

Many somewheres across Black America, we gather around dinner tables with kinfolk — because we got the day off; because aunties, uncles and cousins are always reason enough; because someone will inevitably bring the greens, the baked mac and cheese, and the black-eyed peas, and someone else will grumble about politics. There is always that mumbling uncle whose conspiracy theories make you groan but who would hand you $20 for an empty gas tank without hesitation. And after peach cobbler and sweet potato pie, you may still join that same uncle for an impromptu game of dominoes or, “bones,” as so many of us call them.

Donika Kelly understands the intimacy of that setting. Her new poetry collection, “The Natural Order of Things,” opens with a keen attention to the cultural and familial weight carried by a simple game of bones. That focus becomes clearest in her recurring series “The Bone Museum,” threaded throughout the book. In the second poem of the series, Kelly writes:

“…She say she know and run the board/like she playing for the rent/Say and I’m out/slam the bones hard enough to rattle/to wake up the dead.”

In a recent interview, Kelly said she nearly titled the entire collection “The Bone Museum,” a choice that would have made sense. Bones, literal, imagined, missing, reimagined, appear throughout the book as a central, multiplying image. Their presence and absence anchor the four sections of the collection, which circle forms of love in the broadest, almost Greek sense: self-love, familial love, erotic and romantic love, and the wider love that binds communities. Across all of them, bones follow.

Kelly is masterful in the ease with which she moves this imagery through the book. In “Self-Portrait: A Triptych,” bones reappear in the third section, subtitled “Carapace,” the scientific term for the hard outer shell of many small animals:

“And now my tortoise self.

My crab self.

My tortoise self.

My crab self.

My heavy and old.

My carapace too small.”

Here, Kelly is at her finest. The tortoise’s protective burden and the crab’s confined shell, which must be shed to grow, become metaphors for a body healing from trauma while making space for erotic pleasure. Kelly, a Black queer woman, situates this self-examination among a sequence of lyrical poems exploring queer intimacy and desire. The poems offer an unapologetic celebration of Kelly’s love for her wife.

For readers familiar with her earlier collections, “Bestiary” and “Renunciations,” which address the trauma of her father’s sexual abuse, the use of animal figures as intermediaries between pain and embodiment will feel familiar. In “The Natural Order of Things,” the poem “The moon rose over the bay. I had a lot of feelings.” appears again, this time situated near the center of the erotic section. Its presence invites readers to consider the three books together as a continuum.

“I am taken with the hot animal/of my skin, grateful to swing my limbs,” she writes, a line that, in this new placement, reads less like an ending and more like a turning point.

The recontextualized poem signals a shift in Kelly’s concerns. Trauma is not the focus of this collection, though it remains a distant whisper. Instead, “The Natural Order of Things” attends to love as a regenerative force, one inseparable from the body and the natural world. The world, in turn, becomes a compass guiding survivors toward the possibility of what comes after harm.

In “Every moment I have been alive, I have been at the height of my powers,” a crown of interlocking sonnets, Kelly writes:

“Which ever direction I walk is north,

cardinal. For years now, I have only walked

north. I have walked north into a sun lifting

the horizon like a seedling through soil.”

In these poems, movement becomes healing. Walking north becomes an insistence on survival, on wellness, on moving toward the light even when the past lingers.

Justice, in Kelly’s work, is not courtroom-bound but often imagined, a felt desire to correct everyday violations against Black people in public spaces. In “We Came Here to Get Away From You,” a white woman interrupts the speaker’s quiet moment with an exhibit of whale bones to perform grief over the murder of Emmett Till. The poem ends with a startling line: “…I wanted/to hold her shoulders, vomit into her mouth.” The visceral rejection underscores the exhaustion of racial intrusion. Other politically aware poems, such as “What I Might Sing” and “I never figured out how to get free,” offer similar moments of communal recognition and resistance.

Still, Kelly grounds the collection in love’s perpetual capability. In “Major Arcana,” she writes:

“This weather, unreasonable

this longing, yet both–

one alongside the other–

companions for the day’s

practice: a praise song

to youth and I love you,”

If Mary Oliver and Audre Lorde had a queer literary descendant, one could imagine her writing poems like Kelly’s. With clarity, lyricism and deep care for the natural world, Kelly invites readers to find themselves in the vastness around them. She writes to the marrow of what it feels like to be human in uncertain times, reminding us to center our loves, our bodies and the reveries that surround us.

“The Natural Order of Things” urges us to marvel at how the world’s inherent kinship reverberates back through us, felt, as Kelly would say, deep in our bones.

Copies of “The Natural Order of Things” are available at www.donikakelly.com.

Sagirah Shahid is an award-winning poet and was a finalist for the city of Minneapolis’ position of poet laureate. You can find more about Shahid’s writing at https://www.sagirahshahid.com.