Conclusion of a two-part story

The City of Detroit’s motto translated from the Latin is “We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes.” That motto is prominently displayed on the city’s flag and has been the impetus for city residents ever since the 1805 fire that destroyed the city.

The executive director of Arise Detroit and longtime Detroiter Luther Keith has been an active participant in various “reflective” panel discussions about the summer 50 years ago that he and others lived through and experienced the last week of July 1967. Keith is a retired local journalist who was born in Detroit and has lived there most of his life.

“I was on a panel that played on C-SPAN,” he told the MSR. He said the ’67 civil disturbance was a “very jarring look” at police-community relations in Detroit and the summer’s urban unrest was a boiling point moment.

The oft-asked question in its aftermath, then and now, is “Was it a riot or a rebellion?”

“There were some people who were just rioting, reacting to police oppression,” said Keith. “Some people who just rioted just to get stuff.”

Historian Herb Boyd called it a rebellion “because there were class elements rather than race elements.” Boyd devoted a chapter to the 1967 occurrence in his new book Black Detroit. He described the contributing factors as “racial history, the abuse of the cops, the unemployment situation, and the housing dilemma. There were a number of continuing elements of despair, waiting for a moment to explode. All they needed was that particular night for that civil disturbance to occur.”

The Black Detroit press release noted how Boyd chronicled the city’s history through “personal experience, exhaustive research, and stories gathered from the city’s archives and griots to convey African Americans’ significant influence on Detroit’s rich history.” But the city’s racial tensions have existed ever since Detroit was founded as a French trading post before America became a country.

Slavery existed in Detroit for a time, said Boyd. Black city residents once helped a husband and wife — former slaves — escape from jail and cross the river to Canada. The couple would have been returned to the South and to their slave masters. The residents were later falsely blamed for setting the jail on fire, which resulted in the city’s first riot in 1830.

Where is Detroit today, post-1967?

The disturbance left the Motor City economically and socially scarred. “We lost businesses,” said Keith. “White people didn’t want to live in Detroit. They took their money and the tax base [elsewhere]. They moved out to the suburbs.”

Such population shifts, according to Boyd, began in the Motor City as early as the end of World War II when nearly a million and a half Whites left Detroit. The city eventually became not only a Black majority urban center but a seemingly subservient minority to the surrounding suburbs “in wealth [and] in commerce,” said Boyd, quoting the late Coleman Young, Detroit’s first Black mayor, who served for 20 years.

History has shown that Detroit has found a way to survive its crises and emerge stronger, as the hopeful motto on its flag says. Most recently it survived bankruptcy and the state’s four-year-long takeover when Republican Governor Rick Snyder appointed Kevyn Orr as emergency manager in 2013, over the elected mayor and city council.

Some, perhaps including the state legislature in Lansing, still see the Motor City as being a “financial ward” of the state for many years to come. “Detroit will never be what it was,” bemoaned Keith.

“Detroit has been through the fire so much… I do think that [with the] lessons of ’67…we have to work for a more just, equal opportunity society. That’s still a big issue in Detroit.”

After three decades of Black leadership in City Hall, Detroit now has a White mayor. Talk has resurfaced of moving the city from a standalone government to a regional form of government where the richer surrounding suburbs would have a majority say in city affairs.

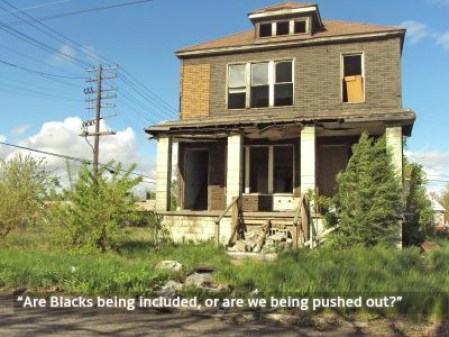

Downtown has been revitalized, and millennials are moving into the city. Some are buying up abandoned properties for far less than market value and rebuilding them for themselves or for resale. Meanwhile, many of Detroit’s inner-city neighborhoods look like ghost towns.

“Are Blacks being included, or are we being pushed out?” asked Keith. “Who is Detroit being saved for? That’s a big discussion.

“I contend that it is still a great city.” While his hometown is not perfect, he said, “it can still be great. “The most important thing is to learn and listen to the people. If you do that, you can figure some things out.”

Information from Herb Boyd’s Black Detroit was used in this report.

Charles Hallman welcomes reader responses to challman@spokesman-recorder.com.

Related content:

Support Black local news

Help amplify Black voices by donating to the MSR. Your contribution enables critical coverage of issues affecting the community and empowers authentic storytelling.